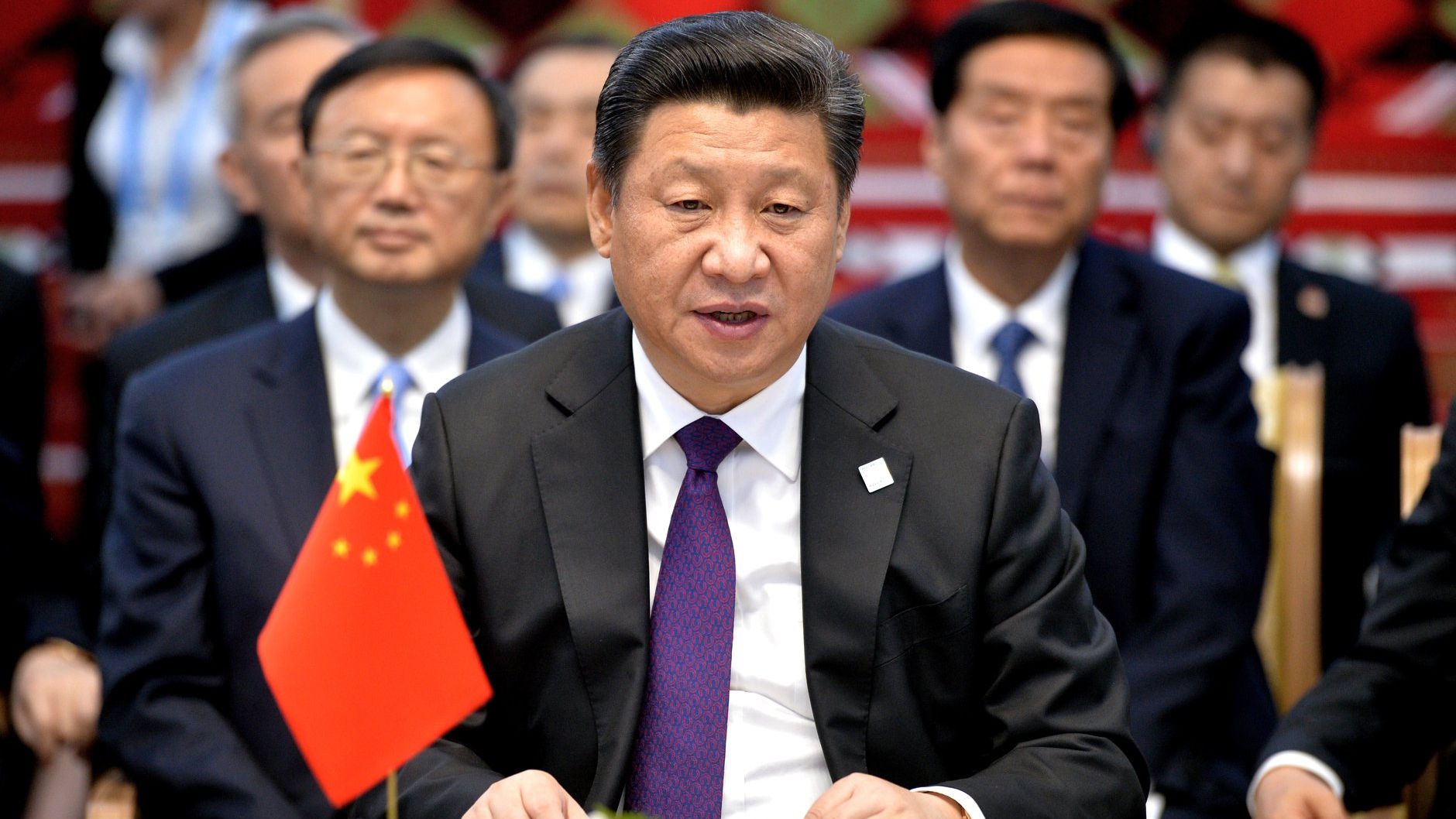

President Xi Jinping is determined to bring major Chinese companies to heel, and not just in the high-flying high-tech sector. That much is clear. In an August 17 speech to the Central Commission for Financial and Economic Affairs, he called for “common prosperity for all” as a fundamental requirement of socialism. The meeting called for regulating high incomes and exhorted the rich to “give back” more.

By Gregory F. Treverton

Note: The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of SMA, Inc.

What is less clear is why the turn against the market economy, and why now. While the evocations of Mao and the Cultural Revolution are surely off the mark, the turn against the rich carries broader implications for the future of the Chinese economy—and its politics.

Old Methods, New Targets?

The speech followed a string of actions against companies that began with high-tech and then spread. In November 2020, the government abruptly prevented an initial public offering (IPO) by Ant Group, and the firm’s rock-star founder, Jack Ma, vanished from public view. In July this year, the ride-hailing company Didi Chuxing was the target of regulatory investigations just before its IPO, which sent its stock price plummeting. Later that month, the State Council outlawed for-profit companies and foreign-invested companies from much of the educational sector, and regulatory initiatives then spread to the entertainment sector.

In late August, Zheng Shuang, one of China’s best-known actresses, was fined almost $50 million for tax evasion. Zheng had been involved in several scandals this year over high pay and alleged ethical lapses. The same month, all references to Zhao Wei, a billionaire actress and friend of Jack Ma, disappeared from Chinese social media and streaming sites. These actions appeared as a strike against glamorizing wealth, with Zhao and Zheng cast as the day’s villains in the pursuit of common prosperity.

On September 3, the Party’s propaganda department published “Comprehensive Management in the Cultural and Entertainment Field,” which proclaimed that the Party had a responsibility to manage public opinion in both its positive and negative effects. Previous efforts to carry out “large-scale rectification…have achieved certain results,” and the time was now ripe for “comprehensive management” of the entertainment sector to ensure adherence to “socialist core values” and to “maintain market order.” A long list of subsequent instructions to broadcasters gave a sense of how far-reaching the controls would be, including bans on “sissy boys” and “stars with lapsed morals.”

In one sense, Xi’s speech can be seen as business as usual, pun partly intended, not an important change in economic policy. Some of the targets are new, but the regulatory crackdown is not. The Party approaches private sector riches purely instrumentally: when they are seen to serve the Party’s interests, they are protected but never granted rights that cannot be revoked. The Party does not control private companies in the same way it does state-owned enterprises (SOEs) but does use instruments—crackdowns on particular companies or sectors—that run well beyond the familiar tools of western governments, regulation, and joint ownership.

So, too, disappearing capitalist barons are not new. In 2017, Wu Xiaohui, chairman of the insurance company Anbang Group disappeared; six months later, he was formally arrested on corruption charges. Later that year, when property developer Dalian Wanda denied rumors that its chairman, Wang Jianlin, had disappeared and been forbidden to leave China, the group’s shares fell by a tenth. In 2018 Ye Jianming, Chairman of CEFC Energy was detained. For its part, Zheng Shuang’s case echoes that of Fan Bingbing, another highly paid actress who disappeared for three months in 2018 and also received a hefty fine for tax evasion.

How Much Continuity?

So, too, it is possible to interpret Xi’s speech as merely the latest turn in a continuing dialect of communist logic. For instance, this past June Xi declared that, after a century, the Party had achieved its goal of creating a “moderately prosperous society” in which people have the means to live comfortably. This made the long-standing “moderate prosperity” slogan out of date, and in that sense “common prosperity” is just the logical, and kindred, follow-on to “moderate prosperity.”

The Party’s doctrine encompasses a concept called the “principal contradiction”—the central tension that drives history at any stage, and thus becomes the key issue that the Party must confront. Mao’s reformist successor, Deng Xiaoping, identified “material and cultural needs of the people versus backward social production” as the principal contradiction, and thus the basis for forty years of emphasis on rapid economic growth to meet people’s basic needs.

At the 19th Party Congress in 2017, Xi changed the principal contradiction, which is now between “the ever-growing needs of the people for a better life and unbalanced and inadequate development.” By that reading, the shift toward a more egalitarian, hence redistributive, agenda was in motion at least by 2017. Against this background, “common prosperity” looks less like a radical new direction and more like the return to an agenda that had been eclipsed by the trade war with the United States and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Still, the puzzle of ‘why now?’ persists. We know that Xi is a man in a hurry. While China seems to many western observers a country on a roll, Xi seems to know that roll is slowing—or heading for a demographic cliff. China’s work force peaked in 2015, and now Xi’s race is to make China rich before it becomes old. On those grounds, this seems to an odd time to strike out against those who demonstrate China’s success—and also perhaps also create its innovation.

Perhaps, China’s government capitalism will continue to target only a few ostentatious examples: the watchword for those elsewhere in the world fighting corruption is “fry a few big fish.” Next year’s Party Congress comes as an especially sensitive time, including for Xi’s continued leadership, so perhaps the crackdowns are meant to show he is clearly in charge in advance of the Congress.

But perhaps, just perhaps, Xi worries that he will fail in making China rich before it is old, and thus the economic legitimacy of the regime can’t rest on riches but rather must promise some equality—a decent life for more Chinese, not the high life of the princelings and Jack Mas. Perhaps. Stay tuned.